In spring 2020, districts across the country had to shift almost overnight from in-person school to remote learning. With no time for planning, teachers and students alike found remote learning challenging. Fortunately, many lessons have been learned from last spring’s experience. While we hope all districts will be back to in-person learning soon, districts and schools will need to be flexible and may have to pivot among remote, hybrid, and in-person instruction models this academic year. With this in mind, we have compiled, based on research and our reopening work with more than 70 districts over the summer, some key practices to help make learning impactful and engaging during periods of remote instruction.

- Take the time to develop remote-learning norms and create an inclusive classroom culture

- Invite five students per week to a virtual breakfast or lunch group.

- Carve out 15 minutes twice a week for relationship-building activities. Districts should provide teachers with a sample list of activities to consider.

- Create remote-learning roles that students can play to take ownership of their learning environment. Examples may include having a “Classroom DJ” who plays music before the lesson begins or designating a “Mood Monitor” who signals the teacher when it is time for a quick brain break.[1]

- Develop “classroom logo” virtual backgrounds that students co-create. Having a common virtual background can help preserve student privacy and minimize the distraction of background activity.[2]

- Prioritize clarity and organization on learning platforms

- Intentionally organizing a place where students can find classroom materials, activities, notes, and homework assignments. This site should be kept consistent and updated frequently regardless of pivots among in-person, hybrid, or remote instruction models.

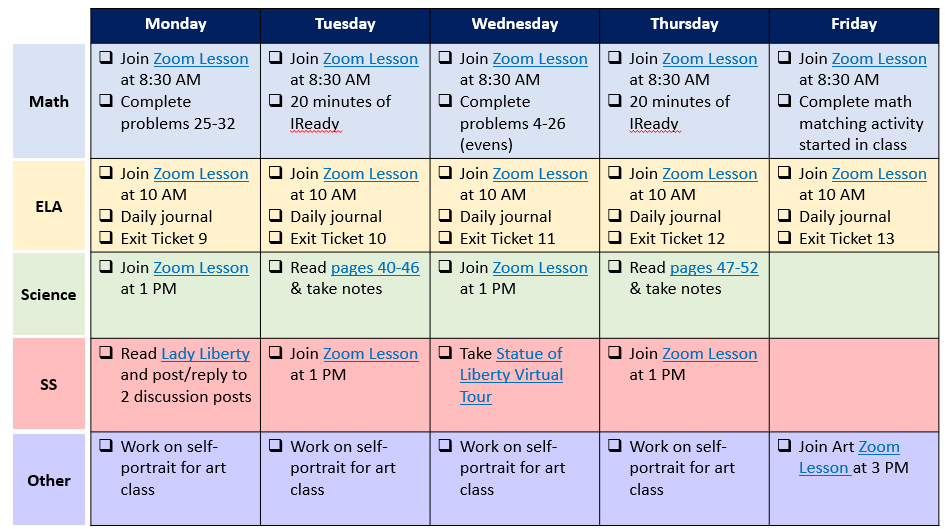

- Developing a weekly student-facing task list that maps out everything a student needs to do for each subject by day of the week.[3] (See Exhibit 1).

- Creating customized directions using short videos and audio recordings in addition to written instructions.[4]

- Leverage the capabilities of the remote instruction platform and use a variety of short segments to increase student engagement in synchronous learning sessions

- Breakout rooms for small-group discussions or turn-and-talks

- Having students share their screen and present/share to the class

- Having students collaboratively create documents via Google Docs, assigning sections and roles to different students

- Develop a plan for students’ asynchronous work that prioritizes choice and creation

- An opportunity to create something rather than completing traditional summative assessments. For example, having students tackle project-based learning assignments, create short videos, or develop a lesson to teach the rest of the class.

- Material that is relevant to situations or experiences students encounter outside of school to increase engagement in the assignment.[6]

- Assignments that provide structures and milestones to help students better manage their time and receive feedback as they learn. For example, building in checkpoints so the teacher can proactively provide feedback before the due date.

- Create a System for Grading, Assessing, and Providing Feedback on Student Work to Emphasize the Value of Remote Instruction and to Value Student Work

- Recording video or audio feedback for the student to help clarify any frequent misconceptions the teacher is seeing.

- Setting expectations for when students can receive feedback on their assignments.

- Committing to replying to students’ emails, calls, or texts within a set amount of time during the school day if the school is fully remote.

This academic year, it is important for teachers to take the time to develop classroom norms and create a classroom culture that will be enduring regardless of pivots among remote, hybrid, and in-person models. Teachers should intentionally involve students in the process as much as possible. Ideas for creating remote classroom norms and building an online classroom culture include the following:

Creating an organized classroom and providing clear instructions are staples of every effective classroom. Teachers should continue using the research-backed strategies that they utilize during in-person instruction in their remote classroom environment, such as posting frequent reminders when new assignments are released, proactively communicating upcoming due dates, and providing students with common expectations for their work.

However, unlike previous school years, students will also want and need more organization than is typically necessary in an in-person learning environment. Teachers may consider

Exhibit 1: Sample Weekly Student-Facing Task List

Live, synchronous instruction can be the most impactful format for teaching new content or intervention; however, teachers should not simply try to replicate their traditional lessons and materials in an online setting because "Zoom fatigue" sets in fairly rapidly. Instead, lessons should be restructured so that live video-conferencing sessions are limited to 45 minutes.[5] For the live lessons, teachers should try breaking lessons into five-to-ten-minute segments alternating between modalities. Sample modalities include

Whether the model is hybrid or fully remote, students will likely be asked to complete asynchronous work. While many schools provided students with asynchronous work in the spring, most of it focused on task completion or filling in worksheets. Teachers or curriculum coaches should instead develop assignments that prioritize choice and creation rather than completion. The following types of assignments should be considered:

A major critique of remote instruction during the spring of 2020 was that some students did not take coursework seriously. Student surveys revealed that many students at all grade levels inferred from the lack of grading, assessment, and feedback on homework that remote instruction was not as real as in-person schooling.

For remote instruction to be successful, a system must be in place to grade student work or provide feedback. Teachers may consider

Many of these key practices simply adapt to a remote-learning environment strategies that teachers have previously mastered. While the assignment turn-in bin may now look more like an attachment to an email, and turn-and-talks require a bit more coordination, the instructional foundation of building teacher-student relationships and adapting content to students’ needs will still remain. Districts that work alongside teachers to focus on these key practices will help the school year be one to remember, for both its strong academics and its novelty.

NOTES

[1] Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, and John Hattie, “Distance Learning Up Close: Teaching for Engagement and Impact in Any Setting,” webinar from Edweek, July 23, 2020,

[2] Julie Kennedy and Christy Lundy, "Remote Start: Beginning the New School Year Virtually," Medium, July 30, 2020, https://stories.chartergrowthfund.org/remote-start-beginning-the-new-school-year-virtually-12512a8e5a05.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Fisher, Frey, and Hattie, “Distance Learning.”

[5] Emma Dorn, Frédéric Panier, Nina Probst, and Jimmy Sarakatsannis, “Back to School: A Framework for Remote and Hybrid Learning amid COVID-19,” McKinsey & Company, September 2, 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/back-to-school-a-framework-for-remote-and-hybrid-learning-amid-covid-19.

[6] Fisher, Frey, and Hattie, “Distance Learning.”